superchuck500

U.S. Blues

Online

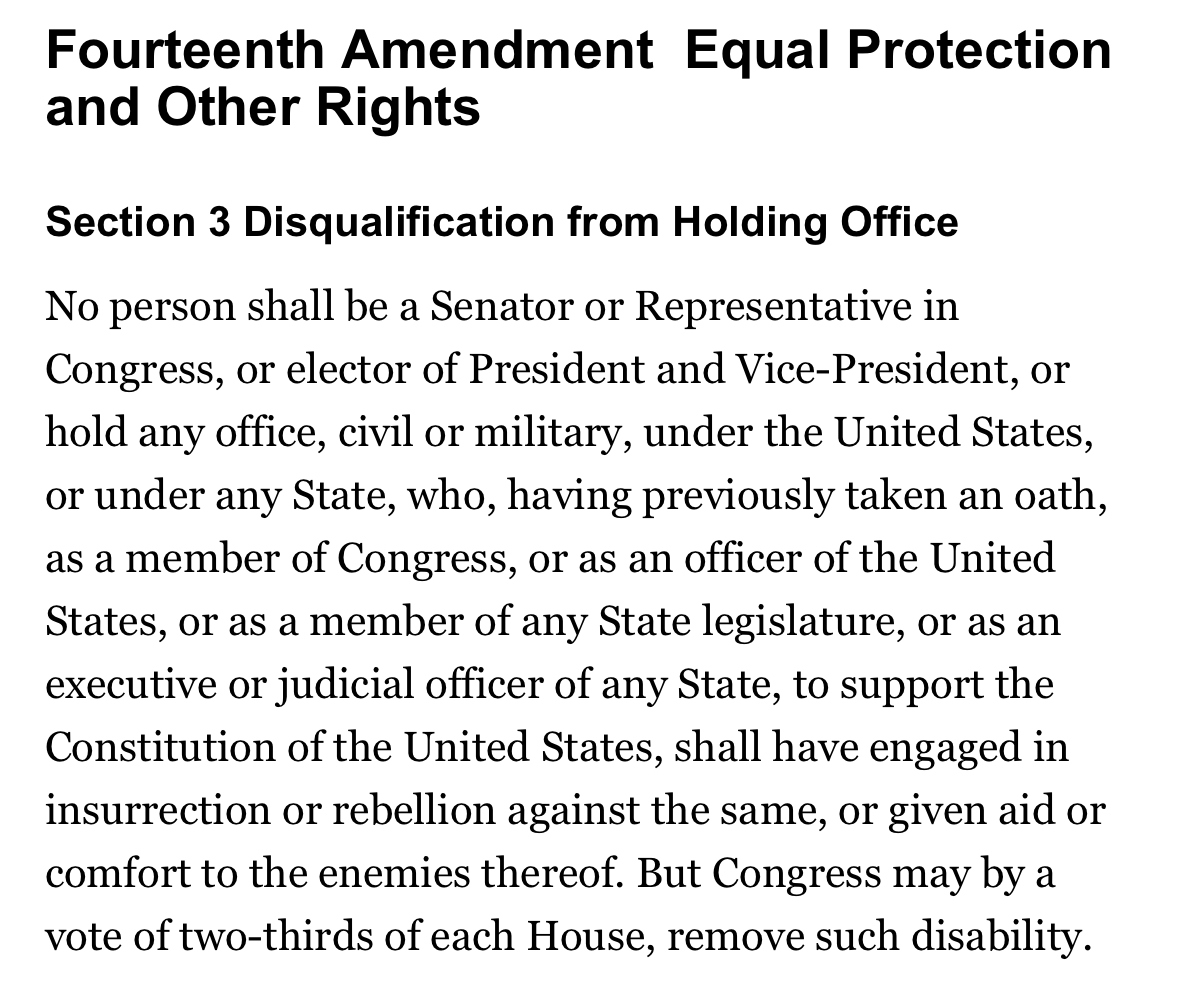

Section 3 of the 14th Amendment:

There is a growing movement in some states to conclude that Trump is already disqualified under the 14th Amendment and they may remove him from the ballot. This would set-up legal challenges from Trump that could end up at the SCOTUS.

The 14A disqualification doesn’t have any procedural requirements, it simply says that a person that does those things can’t serve in those offices. It a state says it applies to Trump, it would then be on Trump to show that it didn’t (either because what he didn’t doesn’t amount to the prohibited conduct, or that president isn’t an “officer” as intended by the amendment).

States are in charge of the ballots and can make eligibility determinations that are subject to appeal - there is actually a fairly interesting body of cases over the years with ballot challenges in federal court.

More on the legal argument in favor of this:

www.theatlantic.com

www.theatlantic.com

There is a growing movement in some states to conclude that Trump is already disqualified under the 14th Amendment and they may remove him from the ballot. This would set-up legal challenges from Trump that could end up at the SCOTUS.

The 14A disqualification doesn’t have any procedural requirements, it simply says that a person that does those things can’t serve in those offices. It a state says it applies to Trump, it would then be on Trump to show that it didn’t (either because what he didn’t doesn’t amount to the prohibited conduct, or that president isn’t an “officer” as intended by the amendment).

States are in charge of the ballots and can make eligibility determinations that are subject to appeal - there is actually a fairly interesting body of cases over the years with ballot challenges in federal court.

More on the legal argument in favor of this:

The Sweep and Force of Section Three

Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment forbids holding office by former office holders who then participate in insurrection or rebellion. Because of a range

papers.ssrn.com

The Constitution Prohibits Trump From Ever Being President Again

The only question is whether American citizens today can uphold that commitment.

Last edited: