V Chip

Truth Addict

Offline

Two Justices Say Supreme Court Should Reconsider Landmark Libel Decision (Published 2021)

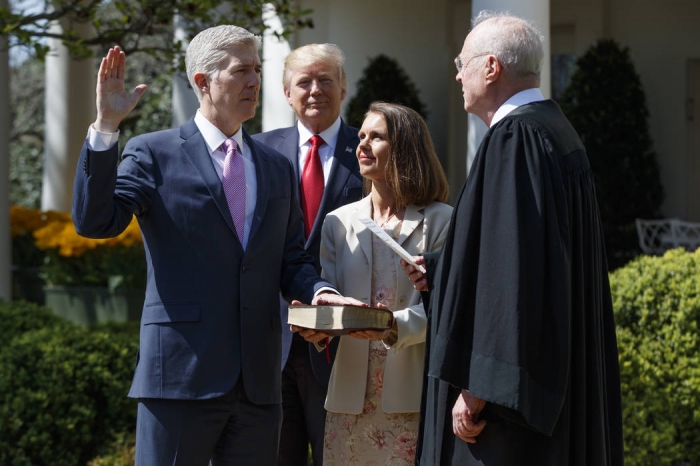

Justice Neil M. Gorsuch added his voice to that of Justice Clarence Thomas in questioning the longstanding standard for public officials set in New York Times v. Sullivan.

I found this part of Gorsuch's dissent interesting.Two justices on Friday called for the Supreme Court to reconsider New York Times v. Sullivan, the landmark 1964 ruling interpreting the First Amendment to make it hard for public officials to prevail in libel suits.

One of them, Justice Clarence Thomas, repeated views he had expressed in a 2019 opinion. The other, Justice Neil M. Gorsuch, offered fresh support for the view that the Sullivan decision and rulings extending it warranted a reassessment.

Both justices said the modern news media landscape played a role in their thinking about the actual malice doctrine announced in the Sullivan case. That doctrine required a public official suing for libel to prove that the offending statements were made with the knowledge they were false or with serious subjective doubt about their truth — a stricter standard than is applied to cases brought by ordinary people. The doctrine was expanded in later court rulings to cover public figures, not just public officials.

I find that interesting, because to me both are arguing in direct opposition of their supposed deepest Constitutional beliefs -- that of Originalism. The two most devout originalists on the court are now saying basically that the founders and the prior court decisions could not have forseen the way things would change, and thus we need to rethink the freedoms of the press and the landmark cases that have decided First Amendment protections and handling libel suits.The Bill of Rights protects the freedom of the press not as a favor to a particular industry, but because democracy cannot function without the free exchange of ideas. To govern themselves wisely, the framers knew, people must be able to speak and write, question old assumptions, and offer new insights. “If a nation expects to be ignorant and free . . . it expects what never was and never will be. . . . There is no safe deposit for [liberty] but with the people . . . [w]here the press is free, and every man able to read.”

[...]

Since 1964, however, our Nation’s media landscape has shifted in ways few could have foreseen. Back then, building printing presses and amassing newspaper distribution networks demanded significant investment and expertise. [...] Broadcasting required licenses for limited airwaves and access to highly specialized equipment. Comparatively large companies dominated the press, often employing legions of investigative reporters, editors, and fact-checkers. But “[t]he liberty of the press” has never been “confined to newspapers and periodicals”; it has always “comprehend[ed] every sort of publication which affords a vehicle of information and opinion.” And thanks to revolutions in technology, today virtually anyone in this country can publish virtually anything for immediate consumption virtually anywhere in the world.

[...]

The effect of these technological changes on our Nation’s media may be hard to overstate. [...] It’s hard not to wonder what these changes mean for the law. In 1964, the Court may have seen the actual malice standard as necessary “to ensure that dissenting or critical voices are not crowded out of public debate.” [...] But if that justification had force in a world with comparatively few platforms for speech, it’s less obvious what force it has in a world in which everyone carries a soapbox in their hands. Surely, too, the Court in 1964 may have thought the actual malice standard justified in part because other safeguards existed to deter the dissemination of defamatory falsehoods and misinformation.

Is it just me, or is that really the essence of what they are arguing?